Welcome to what I hope to be a very enjoyable blog, all about the words of the dictionary. The dictionary of reference will be ‘Dictionary.com’.

Friendly Disclaimer: For the purposes of this blog, and for my own sanity, a word here will generally be defined – and this is a very very loose definition – as an adaptation of the previous word in the list where there is no space or non-letter (e.g. a full stop, a hyphen, a number etc.) between the previous form and the next form going down the list. And initialisations and acronyms don’t count either. Though I’m not counting those, I will be including Proper Nouns (because that can feed into my main genealogy blog too).

Simply, after ‘a’, the next ‘word’ on Dictionary.com is ‘aa’, then ‘Aachen’, then ‘aah’, then ‘Aalborg’, and so on and so forth.

Alors, allons-y!

Word 14: Aarhus

Aarhus! Nothing to do with Madness’ similar-sounding 1983 single, I should note. Aarhus is our next location on our exploration through the alphabet! As with our previous exploration of Aalborg, Aarhus is also in Jutland, and is the largest city there (as well as being the 2nd largest city in the whole of Denmark!). With its own Bay named after it (tucked in nicely as an extension, in a sense, of the Kattegat, between the North and Baltic Seas), and with a rapidly growing demographic of young people – the largest age group is 20-29 year olds -, Aarhus is a particularly important city for Denmark. No wonder it’s nicknamed “Smilets by” – or ‘City of Smiles’! As always, here’s a map showing precisely where Aarhus is, and a nice picture of the city. The diversity and expressiveness of the city is so evident from this viewpoint alone!

Being right by the water (and served by the ‘Molslinjen’ Ferry Service) is so important for Aarhus, and makes it the largest container port in Denmark. As a sidenote: ‘Port’ in Danish is ‘Havn’, as in Faroe Islands’ ‘Tórshavn’ (and cognate with Swedish ‘hamn’ [as in ‘Mariehamn’, in the Åland Islands]). This is a good trick to remembering the general location of those places!

Anyhow, so what’s so important about Aarhus? In terms of it being the largest container port, Aarhus is so useful for Denmark’s imports and exports, both to its nearby countries and elsewhere. Companies have really made use of its location, with Jysk and Arla Foods being just two of the companies whose headquarters are located in Aarhus. As a major city, it functions just as successfully and swimmingly as other city, with a massively strong cultural scene, which has led to it taking more monikers than just Smilets by. Perhaps my favourite is ‘Verdens mindste storby’ – ‘World’s Smallest Big City’. For me, that sums up precisely what Aarhus is about; an exciting haven of culture, wonder and diversity, all neatly compacted into one small city in Jutland.

Of course, this is a language blog at heart, and so let’s have a look at the etymology of Aarhus. I think it’s useful to remind ourselves what’s so prevalent about the onomastics of ‘Aa-‘ locations, and that is the very simple fact that ‘Aa’ and ‘Å’ are quite regularly the same idea, such that we should consider ‘Aa’ to have the value of one letter. Why is this particularly notable? Well, it’s very standard to see place names that have either Aa or Å, and this can be more political than we might expect.

‘Aarhus’ is a great name from a linguistic point of view. With even an ounce of Germanic knowledge, it might seem fairly self-explanatory: ‘Aar hus’, where ‘hus’ means ‘house’ (which it indeed does), and then ‘Aar’ is just part of the name, right? Right?

Not quite.

You see, Aarhus is actually named after the river nearby – Aarhus River (or ‘Aarhus Å’ in Danish). The name is actually a compound of the Danish words ‘ár’ (the genitive of ‘á’ (=river)) and ‘oss’ (=mouth, specifically in rivers). So yes, Aarhus is pretty autological. It is literally a river mouth… at the mouth of a river. Nothing to do with a house! It seems that ‘oss’ isn’t used so much to mean ‘mouth’ in modern Danish, but in modern Icelandic we do find the word ‘ós’, which refers to a ‘river delta’. Similarly, Icelandic ‘á’ can mean ‘river’, as well as a whole array of other words. This is, of course, a highly enjoyable feature for Icelandic learners.

There’s even more to this wonderfully simplistic-but-complex word though. In 1948, Danish underwent a spelling reform (though as many a Danish speaker will tell you today, it can sometimes feel that the phonology and orthography of Danish rarely go hand in hand!). Amongst those spelling reformations included the preference of the Swedish ‘Å/å’ instead of ‘Aa’. So, of course, it was most common for Aarhus to be written as ‘Århus’, instead of ‘Aarhus’. Notably, some Danish cities did stick with Aa in the first place, including Aalborg (which I’ve already written about!). Ever the progressive city, Aarhus embraced these rules. But then, in 2010, the city council re-progressed their progressiveness, and switched back to ‘Aarhus’, in order to strengthen the international profile of the city. Given the exquisiteness of the city nowadays, I think it’s safe to say that’s been a good idea! There are still remnants by institutions and organisations of the Å, as in the ‘Statsgymnasium’ and the news media ‘Århus Stiftstidende’.

So, whether you opt for ‘Aarhus’ or ‘Århus’, there’ll be at least someone who will appreciate your spelling – but maybe stick to Aarhus on official documents!

Next, we will delve into something completely different. We’ll still have names – but not place names! Nope, people’s names!

Farvel, mine venner!

Word 13: Aargau

It is 2nd January, and with a new year comes new opportunities to write about words in the alphabet! It also gives me a good reason to, well, get back to this blog… but let’s skim over that part

So where are we today? Well, in blog posts gone past, we spent most of our time in Scandinavia, with a little detour amongst the plants of Hawaii, and we did even pop into Switzerland for a bit. Well, after we’ve avoided the aardvarks and aardwolfs of the world, we’ve found ourselves back in Switzerland. And we don’t even need to worry about Brexit. (There is something else to worry about though. You know, that big thing…).

ANYWAY.

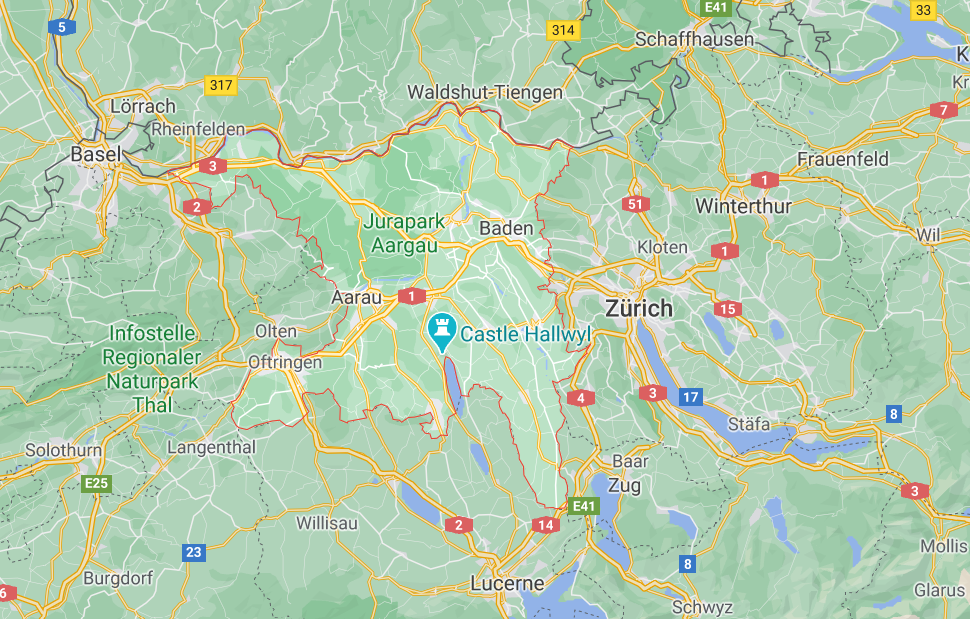

We find ourselves in Aargau, a canton in northern Switzerland. As with all the place names, here’s a nice map and some equally nice pictures. Eagle-eyed readers will notice the town of ‘Aarau’. This is indeed the Aarau which I wrote about, and in a little while, we’ll look at the linguistics behind Aargau (which, I think, is pretty interesting!), and its differentiation from Aarau – but crucially, both of them derive from the River Aare.

Aargau is one of the more northerly cantons of Switzerland, close to Zurich (but being home to the city of Baden), and is one of the most densely populated regions of Switzerland. It’s a very historical region, its area controlled by the Helvetians (a Swiss plateau-based Celtic tribe), then the Romans, then the Franks during the 6th Century (and its Frankish influences are clear even today). Now, during the Frankish Empire, the area of ‘Aargau’ at the time was an attested border between the Aare and Reuss rivers, and in fact, a lot of what was Aargau then is actually now in other cantons of Switzerland. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the history since then has been complex for Aargau, with its borders being redefined over and over again, and, in 1415, it was invaded by the Old Swiss Confederacy. This was a pivotal time for Aargau, as, once Baden had been taken by a Swiss army and governed by the Swiss Confederation (akin to modern Switzerland), Aargau and its nearby canton of Bern were of great importance to each other, such that Bern’s portion at the time became known as the ‘Unteraargau’, contrasted with the ‘Oberaargau’. It is not too difficult to see what both parts refer to (and we can thank Germanic linguistics for that!). One of the key historical facets of Aargau was its Jewish history in the 17th Century. The only federal condominium where Jews were tolerated at the time, Aargau was the location where the first synagogues were built in Switzerland, in Lengnau and Oberendingen, and this was, at the time, where virtually the entire Jewish population of Switzerland resided, even throughout the 18th Century too.

What of Aargau today? It’s official website states it to be “an attractive and varied place to live and work” – but of course they’d say that. It’s a predominantly flat region overall, with three rivers – Aare (from Bern), Limmat (from Zurich) and Reuss (from Lucerne and Zug) – converging at the aptly named ‘Wasserschloss’ (‘Water Castle’) near Brugg. It seems an idyllic area, with peace and relaxation a-plenty. I’d love to hear from people who live in Aargau – if that’s you, please feel free to get in touch!

Now for the exciting part. The etymology of Aargau is nice and simple, and equally interesting! Let’s remind ourselves about what we learnt about Aarau, the municipality located within Aargau. Though the etymology of Aarau is somewhat unclear, we can certainly see rural denotations – deriving from the river Aare, could it be related to sheep or floodplains (both of which can be translated as ‘Au’ (hence the last two letters of Aarau)). The general idea is slightly similar with Aargau, but also very different! Aargau isn’t just the same word as ‘Aarau’ but with a <g>. Far from it, in fact! You see, whilst Aargau also takes its name from the river Aare, the ‘gau’ is actually a particularly important suffix. A small aside: a fun fact that may come in useful in some incredibly niche quiz – ‘Aargau’ and ‘Thurgau’ are the only two modern Swiss cantons that contain the ‘gau’!

But what does ‘gau’ mean?

Loosely, ‘gau’ refers to a region or province, somewhat analogous to the English ‘shire’. ‘Gau’ is a perhaps surprisingly politicised word – beyond just referring to a region or province, the sheer concept of a ‘gau’ can be seen both during the Carolingian Empire (throughout the 7th Century), divided into ‘Hundreds’, a term which is still used in this way in some areas as far as Australia! In the areas of East Francia where German was spoken, the ‘gaue’ (of course, a plural form of ‘gau’) formed the administrative unit, which was ruled by an aptly named ‘Gaugraf’ (or ‘Gau Count’) during the 9th and 10th centuries. Later on, in the 1920s, ‘gau’ became used to denote regional associations of the Nazi Party, headed by a ‘Gauleiter’. These 33 such gaue were based on Prussia’s states and provinces. Today, whether related to its 1920s connotations, or otherwise, the word ‘gau’ can be seen in numerous place names within (primarily) Germany, Switzerland, Austria and the Netherlands, showing the word’s clear Germanic history at the very least.

I think it’s time to gau away from Aargau now, and next time we’re going to head to Jutland once again!

Auf wiedersehen.

Word 12: Aardwolf

As is perhaps expected for a word that’s so similar in etymology to the one preceding it – ‘aardvark’ – this is only going to be a very short blog post.

It’s quite evident how the word ‘aardwolf’ is formed, with or without prior knowledge from the aardvark. Literally ‘aard’ – ‘earth’ and ‘wolf’ – ‘wolf’. That’s, effectively, all there is to it. It’s an ‘earth wolf’, and ‘wolf’ is the same as in English.

See, nice and short. Next, we’ll be going back to the locations!

Word 11: Aardvark

We come to the eleventh word in this list, but it’s perhaps the first ‘word’ that we would otherwise come across in, say, a standard English-language concise dictionary. Nonetheless, we continue our journey, and head south way more, all the way to South Africa, home of the aardvark. When I first began an alphabet blog a number of years back on Tumblr – yes, I delved into such craziness! -, this was the first word I looked at. Sadly, as I deleted the blog entirely, and have no saved copy of it, I do not retain a single thing from it! Aah no!

I dare say that the etymology of ‘aardvark’ is fairly well known, much more so than its very similar counterpart ‘aardwolf’, from much the same general etymology. It is of Afrikaans and/or Dutch origin fundamentally, two languages which constantly get compared and contrasted (for good reason, some would say). National Geographic claims that the word “comes from South Africa’s Afrikaans language”, as do OneKindPlanet and the Kapama Blog. However, Sabina Nedelius (The Historical Linguist Channel) just this year regarded its etymology from being Afrikaans Dutch, and Language Trainers USA say its ‘from Dutch via Afrikaans’. So should we consider it as being derived from Afrikaans, Afrikaans Dutch, or Dutch? Or maybe even none of them? (OK, even I’ll admit that’s very outlandish!). There is, however, the phrase ‘South African Dutch’ to take into consideration too (where Kath’s blog on ‘For Reading Addicts’ claim it to come from).

Literally, ‘aardvark’ is made up of the words ‘aarde’ (earth) and ‘vark’ (pig), so is effectively an earth pig. Though we tend to point it towards being of Afrikaans origin, the headword ‘aardvark’ in the Geddes & Grosset Afrikaans-English dictionary contains ‘(or erdvark)’ in brackets, and, quite surprisingly to me at least, is translated as ‘anteater’ – not the loanword of aardvark.

If we separate ‘aardvark’ into its respective parts – ‘aarde’ (or, perhaps, ‘erd[e]’) and ‘vark’ – then we find that, yes indeed, ‘vark’ does produce the translations of pig, hog and swine, and aarde does, indeed, give us earth, ground and soil. The same occurs with ‘erd’ – ‘earth’ is the English translation. Aardvark doesn’t appear in the English-Afrikaans section as a headword either, however, in the exact same way, ‘anteater’ does appear translated as ‘aardvark’.

The same situation exists in Dutch with the words – ‘aarde’ and ‘varken’ meaning ‘earth’ and ‘pig’ respectively.

Does that mean, therefore, as ‘aardvark’ means ‘earth pig’ in Afrikaans and Dutch both, that the word is derived from both languages?

Well, yes and no.

As with many etymologies, words tend to derive through several languages – if we use ‘aardvark’, then our best option really would just be to go back to Proto-Indo-European, as Afrikaans and Dutch are both modern languages derived from Old Dutch, itself a West Germanic language.

Earth is similar in form to ‘aarde’ (Grimm’s Law (concerning the change in Germanic consonants) helps to explain why the ‘d’ /d/ in Dutch/Afrikaans is ‘th’ /θ/ in English), and there is difference in the vowels – /a:/ in Dutch/Afrikaans, /ɜː/ in English (and r-coloured in some accents).

Though ‘vark’ might not seem a single bit like ‘pig’, we can trace it as coming from Proto-Germanic *farhaz (applying Grimm’s Law again, the ‘/p/’ in Proto-Indo-European *porkós adapts into an /f/, and then Dutch/Afrikaans ‘vark’). This indeed is cognate to ‘pork’ in English (hence how ‘pig’ in Dutch and Afrikaans is ‘vark’)!

In this respect, the etymology appears to be no different whether we consider it as either Dutch or Afrikaans, which is certainly understandable, insofar that they are, as stated above, both West Germanic language. At this point, we might just say that it comes from both, though Afrikaans later than Dutch (where Afrikaans as a language derived from in most, if not all, analyses). Findley and Rothney (2011) discuss the politics of this well and Dutch expansion into South Africa. That’s a key word in this instance – the politics of the situation. It is the politics behind the matter that explains why we might be surprised by the phrase ‘South African Dutch’, when we may well just refer to this as ‘Afrikaans’, and so, given that, we might finally assert that the etymology of ‘aardvark’ is, in and of itself, Afrikaans. It is certainly justified though, to acknowledge that this is ‘via Dutch’ – but, as will likely be the case with many words, we shouldn’t see this as a solely linguistic matter.

And that’s all for today! Vaarwel!

References

Findley, C.; Rothney, J., 2011. Twentieth Century World. s.l.:Cengage Learning.

Webster’s Word Power, 2015. Afrikaans-English English-Afrikaans Dictionary. Glasgow: Geddes & Grosset.

Word 10: Aarau

We have reached the 10th word! Only a couple hundred thousand more to go…

This next stage takes us more southerly from where we were in Finland, and down past Aalst and into Aarau, Switzerland, which refers to either a town, a municipality, or the district. Somewhat humorously, this is itself situated within Aargau (notice the added ‘g’), which has its own headword on our source dictionary, and is, as such, going to be its own blog post. Aar, what fun that will be! (OK, OK). I refer primarily to the town here, but – as long as I don’t get myself mixed up – I’ll differentiate accordingly. So, let’s look at Aarau! Of course, as I always do, here’s a rough map of where Aarau is, and some images to entice you to the area. (Honestly, one day these tourist boards will pay me to advertise their regions!). It’s an absolutely beautiful location, that’s for sure, and very synonymous with what we tend to think of when we think about Switzerland or Germany, and their pertaining regions.

It’s on the Swiss plateau, near a similarly named valley (wow, so many <Aa> places here!) called the Aare, a tributary of the River Rhine. It seems to have diminished in relative importance nowadays, but throughout 1798, it became the Capital of the Helvetic Republic (an early attempt to impose central authority on Switzerland, promulgated by French invaders there). In any case, it’s clearly got a certain historical importance (as do most areas, of course), despite a population of only around 21,000. Though officially German-speaking, the dialect most widely spoken there is an Alemannic Swiss German, more generally spoken by around 10 million within Switzerland.

On a historical note, if you like your national Heritage sites, Aarau is plentiful. There are several catholic churches, a Cantonal Library (that is, the ‘Library of the Canton [Aargau]’) and some parks too. In true European fashion, there’s a shoe museum by the Bally Shoe company there. Because why not!

Aside from that, Aarau doesn’t really have a whole lot to say about it as a location. It’s a lovely little town. Go visit if you can.

Let’s delve, then, into what we’re all here for – the language!

So we’ve already looked briefly at the dialect of German which we consider to be spoken there, which is the Alemannic Swiss German dialect. There is a fair bit from a linguistic perspective that we could very well discuss here, but I’ll make a very short note here about the fact that ‘Alemannic’ (from which, if you know French, you might notice ‘Allemagne’ (=Germany), ‘Allemand’ (=German)) somewhat simply refers to the German-speaking parts of Switzerland, the whole of Liechtenstein, and various facets in the surrounding areas (as well as some dialect speakers in the USA). So we shouldn’t necessarily think of this as an entirely different ‘coded’ language to ‘German’, but a dialect; in this case, a form of the German language with phonetic and orthographic adaptations.

The linguistics of the place name ‘Aarau’ itself is very interesting indeed. It follows German phonological patterns, pronounced as [ˈaːraʊ], as we might expect. Now, we might presume that ‘Aarau’ means something like ‘(place on the) Aare’, and we would be somewhat correct. In German, we find the word ‘Au’ to mean a couple of things – in the Alemannic German, we see ‘Au’ as being ‘ewe’, in German, we can find it referring, as well as being the interjection ‘Ouch’, to a floodplain (though we more commonly find ‘Überschwemmungsebene’ when translating ‘floodplain’). So it could well be that ‘Aarau’ is to do with the ‘floodplain of the Aare’, as it were (in a similar vein to Oxford being a ‘ford used by oxen’ (hence ox-ford). The first recorded instance of Aarau is in 1248 as ‘Arowe’, so I’d be more inclined to say it’s simply derived from ‘Aare’ (that is, the tributary of the Rhine), and that it has simply developed over time to be more akin to the German spelling of today.

That’s it, it would seem for this one. Next time, we encounter a word that many amongst us would probably know as the “first proper word we come across in the dictionary” if we’re being loose with our definitions!

Auf Wiedersehen, Aarau!

Word 9: Aalto

Times are rather complex at the moment in the world, and that seems, to me, as good a time as any to ignite the blog. I don’t want to use ‘reignite’ here on the basis that it never ceased to exist, but rather it’s had somewhat of a slumber these past few months.

The next word in our ever-increasing (ever so gradually) list is ‘Aalto’. The curious thing about Aalto is, unlike most of the ‘Aa-‘ words we’ve come across thus far, that it is not prominent in Scandinavia. Instead, we take a north-easternly, 2,115km trip away from Aalst in Belgium and towards Finland, home of architects, politicians, sportspeople, and universities which all have this name. Now, the word ‘aalto’ is ‘wave’ in Finnish (that is, the noun meaning ‘surge of water’). I will look into the etymology of ‘aalto’ and what we can learn from it a little later.

To begin with, let us look at the definition of ‘Aalto’ on our source dictionary, which, though a primarily English-language dictionary, does have this name as its own headword. We’re certainly going to be taking a round-the-world trip here! Ion Dictionary, ‘Aalto’ is listed as such:

“noun

Al·var [ahl-vahr] ,1898–1976, Finnish architect and furniture designer.”

I find it curious that only Alvar Aalto is noted here, given that there is quite the range of people with the surname. After a cursory browse around, perhaps we would consider Aalto to be the most notable person with this surname. There are in fact 2 other architects alone (on Wikipedia, at least) with the surname Aalto, and I think there’s no harm in looking at this in a little more detail. When we use ‘Aalto’ singularly, we are generally referring to Alver Aalto, and so we should look at him primarily.

‘Hugo Alvar Henrik Aalto’ is his full name, and he lived from 1898-1976. It would appear that, whilst an artist by the definition, he didn’t consider himself to be one, stating that painting and sculpture were “branches of the tree whose trunk is architecture” (Enckell 1998). His career began in the 1920s, when much of the western world was focusing on the idea of building upwards; materials had adapted and, as the ‘Art of Great Gatsby’ blog puts it, the 1920s signalled a “complete one eighty in design”. Not for Alver Aalto, whose work in ‘Nordic Classicism’ (a contemporarily somewhat short-lived style) signalled the beginnings of what became a fruitful morphing throughout time, up until the 1970s, of experimenting with various architecture styles. Something particularly prominent, and a word which we’ll hypothetically come across in the future, is the ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (‘total work of art’, ‘universal artwork’, etc.). In brief, this term refers to the idea that virtually everything is important; both the exterior and the interior, as well as shades, placement, practicality, ad nauseam, are all worth paying attention to in Gesamtkunstwerk. Alvar’s first wife ‘Aino Maria Marsio-Aalto’ (née Mandelin) is also a pioneering architect of Finnish-based architecture, the two of them founding Artek, a furniture and design company still going today. Aino appears to have worked more prominently within design, producing wonderful glassware and furniture. Alvar also married Elissa Aalto who, though not having as big an imprint as either Aino or Alvar himself, did contribute to the architecture of various buildings. Since, there has been an Aalver Aalto Museum set up (which, interestingly, exists in 2 cities – Jyväskylä and Helsinki – but operates across 4 buildings), as well as Aalto University, unsurprisingly named after Alvar, and based in Espoo.

Of course, we mustn’t forget that Aalto is more generally a common Finnish name – Saara Aalto, the Eurovision performer, Jussi and Henri Aalto, two Finnish footballers, and Pentti Aalto, a linguist working on a range of languages, are amongst the several notable people who bear this name. But where does ‘Aalto’ come from?

For that, we should look at this somewhat comparatively. Finnish is widely considered to be similar to languages like Hungarian and Estonian, so in that sense it’s a Uralic language (which is, on the whole, undisputed), but deeper, some (such as Collinder (1965) and Janhunen (2009)) point towards it being within ‘Finno-Ugric’ alongside Hungarian and Estonian, some don’t even claim that to exist, and some don’t make any distinction between Finno-Ugric and Uralic! In essence though, many modern linguists tend to consider Finnish as being within the ‘Finnic’ sub-branch of the Uralic branch. Historically speaking, it is perhaps logical to go backwards in understanding the word ‘aalto’. To start with modern Finnish, there is of course the case of the double <aa> vowel digraph. This is, as one might expect, a signal of a ‘long vowel’, akin to [ɑː], and ‘aalto’ is the nominative form (part of the case system in Finnish, which, much to the delight of learners, has 15 cases…!). ‘Aalto’ as a word, then, isn’t particularly ‘interesting’ as it were, and is pretty regular in the grand scheme of Finnish grammar.

If we compare ‘aalto’ to other Finnic languages, we come across such words as ‘alto’ (Ingrian), ‘ald’ (Veps) and ‘aldo’ (Ludian), but the word is not so similar to the equivalent words in Hungarian (

hullám) and Estonian (‘laine’), though ’ald’ exists in the latter form dialectally in some regions. In Proto-Finnic (’proto-’ languages being, importantly, reconstructions of modern languages) linguists have reconstructed ’*alto’. It would seem that Modern Finnish has lengthened the /ɑː/ vowel. Clearly, therefore, surely ’aalto’ is Finnic through and through?

Somewhat remarkably (though understandably perhaps), we find cognates to ‘aalto’ in other non-Finnic languages, stemming from Old Norse. Icelandic and Faroese both have the word ‘alda’, which potentially enables us to think it might not be as solely Finnic as we initially think.

Aalright (see what I did there?) that’s definitely enough for this one! We head south to a town in Switzerland next time. Hyvästi.

Sources:

- Enckell, Ulla (1998). Alvar Aalto: Taiteilija – Konstnären – The Artist. Helsinki: Amos Anderson Museum.

- Collinder, Bjorn (1965). An Introduction to the Uralic languages. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Word 8: Aalst

I’ve taken a big hiatus from this blog, for a multitude of reasons. Those who follow my Twitter (@LinguistJosh) can very clearly see why that was.

Anyhow, I’m back and I’m writing about more words. Perseverance! (We’re nowhere near the letter P…). Give it around 6000 words and we’ll get there…

We are still only on A. In fact, we are still on Aa…

We have come to ‘Aalst’. Curiously, even though Aalst is recorded in the English-language dictionary, it isn’t an English word at all. This might be intuitive with these ‘Aa…’ words. “Josh”, you might say, “we’ve had Hawaiian words, we’ve had Danish and Norwegian places… why is this worth noting?

Because this is actually a Flemish word – it is, according to the definition, the “Flemish name of Alost”.

“So surely we should just wait until we reach ‘Alost’?”

Incorrect. Aalst is what comes up, so Aalst is what we will discuss.

I had a look at what Aalst/Alost was; I’ll refer to it as Aalst hereafter. And surprise, surprise… it’s a city. It’s a city in Belgium to be exact. A small note to be made here: this blogging malarkey has come in very useful for quizzing. Aalesund came up not long ago in a quiz! As has a’a’. Blog. It’s useful. I have no doubt that Aalst will come up soon as well.

Anyhow, back to Aalst.

Here is the location of Aalst.

Aalst is located in Flanders. Flanders is the Flemish province in Belgium. I feel that there is scope for discussing this in greater detail. So I will.

In virtually all countries (and indeed just areas containing various communities), there will be variation in language. This could be variation in actual languages – for example, how Canada has English parts and French parts – or dialectic variation (such as in China, where Mandarin, Cantonese, Wu, etc. are all considered different dialects). The debate around what constitutes a language and what constitutes a dialect is a massive one (and has been going for decades), but it is one of great importance! It can certainly be applied to Belgium. See, in Belgium, there is a similar situation occurring. Belgium has, at its core, Dutch, French, and German as its official languages. Curiously, though German is an official language, it’s spoken by less than 1Dutch in particular is an interesting situation in Belgium, insofar that the Flemish dialect is the most prominent one (spoken primarily in the areas of Flanders), but there is also the Brabantian and Limburgish dialects. In Belgian terms (though by no means in all situations), the ‘differences’ between [Standard] Dutch (I use ‘standard’ with care there) and Flemish Dutch is in the pronunciation, and, quite strongly in fact, in the lexical differences. I won’t go into detail with it, but I have attached a link to a very simple yet comprehensive article at the foot of the page. Those three dialects can all be found in the Netherlands as well. In any case, Aalst is found within this Flemish Dutch-speaking region, which is why it is of importance to note these dialects.

That aside, let us discuss Aalst itself. Aalst lies on the Dender River, and, as we’ve come across with Aalborg, Aalst refers both to a municipality and the main city found therein. Within the municipality, there are also 8 villages, ranging alphabetically (that’s how we do things here!) from Baardegem to Nieuwerkerken. If you want the other 6 villages, Wikipedia is your friend – although no doubt we’ll come across them at some point. For what it’s worth, the Dender River is 40 miles long, but it isn’t particularly important, at least not now.

Aalst is by no means just a random little town. Sure, there’s nothing quite as Charlemagne-esque as Aachen, and it’s not been subject to any sort of war in the past, but it is a notable place all the same. In fact, whilst researching Aalst, 2 events have happened very recently! Only 3 days ago – at time of writing -, the annual carnival held in Aalst has been removed from UNESCO’s heritage list due to antisemitism. Only 15 hours ago, the Brussels Times reported that an elderly couple sadly passed away as a result of a fire happening within Aalst.

I think this is a poignant place to end the discussion on Aalst. Our next word will be Aalto.

Thank you for reading. Bedankt voor het lezen.

Word 7: Aalii

It didn’t take long for us to leave Scandinavia. In fact, we’ve gone back to pretty much where we came from – Hawaii. Yep, we’ve somehow escaped from the volcanoes to the cold climates of eel-infested Scandinavia, and we’ve returned to that US island state. This particular discussion today focuses on something that I don’t have a great deal of knowledge on – though my BBC Radio 4 listening habits might suggest otherwise -, but which is very interesting nonetheless, and, for once, isn’t a geographical location!

So what is an aalii? Well, it’s this.

Technically, it’s written <‘a’ali’i>, and once again, I’m going to be using <> instead of inverted commas because of Hawaiian morphology. (I love it, really, I promise!). For the sake of closeness to linguistic origins, I’m going to continue to write it as ‘a’ali’i, and my computer isn’t going to like that but, well, tough. Linguist’s gotta do what a linguist’s gotta do.

‘A’ali’i is a “bushy sapindaceous shrub, Dodonaea viscosa, of Australia, Hawaii, Africa, and tropical America, having small greenish flowers and sticky foliage”. (Collins Dictionary)

It is quite possible that you skimmed over that. Don’t worry, so did I the first few times. For those of us who aren’t entomologists, here’s a brief breakdown of what exactly that means.

‘Sapindaceous’ is an adjectival form of ‘Sapindacae’, which is itself a tropical and subtropical family of trees and shrubs. A more perhaps commonly known plant from this family is the ‘soapberry’. As most of you will be aware, though, fauna and flora are grouped in a taxonomic hierarchy, and that is where the ‘Dodonaea viscosa’ comes in. Now seems a reasonable time to mention the ‘Seek’ app. This is one of my favourite apps at the moment in the App Store (and on the Google Play store too). In essence, you can take a picture of a flower, tree, insect, mammal, etc., and the app will do the best to tell you what it is. It can be difficult to get the right angle (particularly with fast-moving animals!), but for what it’s worth, I’d highly recommend it. I thought the Seek app might help me here but it was unable to identify ‘a’ali’i from a picture when I tried.

So, I’ll do my best at elaborating, as someone that scraped a C in GCSE Biology…

All species within the biological world are grouped into a taxonomical hierarchy, which helps us to understand what they are, what families they’re in, and, consequently, how they behave both as a species and with relation to their environments, biological factors, etc. It’s well known, for example, that spiders are arachnids, whales class as mammals, and roses are types of plants. That’s the crux of it.

More specifically though, we can delve in deeper and come across ‘KPCOFGS’ – the seven taxonomic levels in order from most general to most specific (each of which, individually, is called a taxon (from Greek τάξις (=arrangement)). More on that if I ever reach the letter ‘T’… (it’s unlikely, but you never know!).

KPCOFGS refers to ‘Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species’; there are others (such as ‘Domain’), but generally, KPCOFGS seems to suffice to please the world’s biologists.

Here is how ‘a’ali’i fits into this hierarchy (according to Wikipedia):

Kingdom: | |

Clade: | |

Clade: | |

Clade: | |

Order: | |

Family: | |

Genus: | |

Species: | D. viscosa |

A ‘clade’ is (and here’s a word for the genealogists!) monophyletic; is a general group that contains one ancestor and all its descendants. I don’t quite understand it completely in biological terms (I refer you back to my earlier remark – I am anything but a biologist), but if you’re able to explain it in layman’s terms, please do!

Anyway, you may notice from the above chart that ‘Sapindaceae’ comes up in the ‘Family’ taxon (ooh, I feel clever right now), and below that, in ‘Genus’, we come across ‘Dodonaea’. ‘Dodonaea’ then develops (subtaxon…ates? Maybe?) into the ‘Species’ of ‘Dodonaea viscosa’. So that’s where the ‘Dodonaea viscosa’ comes in.

I would develop my description of the ‘Dodonaea viscosa’, but I’ve looked at it, and frankly, I’m not even going to attempt it. It looks nice, has tough and leathery leaves, and can grow up to almost 10 feet. If you want more, it’s all on Wikipedia. Besides, we’re not necessarily talking about ‘Dodonaea viscosa’ here; we’re discussing ‘a’ali’i.

So, we’ve looked at the hierarchy of ‘a’ali’i, and we’ve seen a picture of it, and I’ve tried to develop my weak discussion on it, but to virtually no avail.

Now for what I’m much better at: it’s time to analyse ‘a’ali’i from a linguistic perspective. I’ll refer back to something I wrote during my discussion on volcanic ‘a’ā:

“Hawaiian is an isolating language, which in its simplest form, means that it doesn’t use “inflectional morphology” to show tense, plurality, etc.”

Now, of course, this doesn’t mean necessarily that each letter in ‘a’ali’i has a different meaning. But we can analyse it nonetheless. Now, there’s a very similar word to ‘a’ali’i in Hawaiian – Ali’i. Ali’i is the hereditary line of rulers; ‘a’ali’i is this plant that you’ve been reading about. There’s only really one letter’s worth difference but as we’ve seen before, this can be woefully important. It seems to be quite a challenge to find out about the etymology of ‘a’ali’i as a word; in any case, definitions and etymologies have ranged from the Collins one above to simply “a plant of the Dodonaeae”; it would seem that ‘a’ali’i is, more than anything, simply the Hawaiian name for this particular species of plant from within the Dodonaeae. Notably all the same, ‘a’ali’i appears in the Ke Ola Magazine, wherein it is written that “the name ‘a‘ali‘i has been given to a native Hawaiian plant in the soapberry family (Dodonaea viscosa) because it was considered sacred to Laka, the hula goddess.” Certainly, the morpheme “a” added to <ali’i> (the line of rulers mentioned above) apparently implies “of the royalty”. That doesn’t mean to say that the plant <‘a’ali’i> is specifically a plant of royalty, but it’s definitely food for thought. Curiously, Ke Ola also tells us that another name for it is “’a’ali’i ku makani” – ‘’a’ali’i standing in the wind’. Ward Village echoes this usage of ‘a’ali’i in a sentence: “’Alohilohi ke ‘a’ali’i ka lā” – “the ‘a’ali’i is radiant in the sunshine”. Similarly, the Wehewehe dictionary I used in the last Hawaiian discussion treated ‘a’ali’i as its own complete morpheme. So clearly, it might be best to consider ‘a’ali’i as a complete isolate unit.

And that’s all there is to it. ‘A’ali’i has proven to be one for the linguists, the biologists, and the genealogists. Triple whammy!

References

Ward Village. ‘A’ali’i: The story behind the name. [Online]. [Accessed 28th July 2019]. Available from: https://www.wardvillage.com/articles/a-ali-i-the-story-behind-the-name

Fahs, B. 2015. Healing plants: ‘a’ali’i. [Online]. [Accessed 28th July 2019]. Available from: https://keolamagazine.com/plants/aalii/

Word 6: Aalesund

In just 6 words, we’ve travelled on a’a from the volcanoes of Hawaii, taken a detour through the aachen of Germany, and found ourselves spending time in Aalborg. Well, it’s time to leave Jutland, Denmark, but instead of spending 21 hours on a plane ride back to the USA, we’re just going to head 881 kilometres north, ending up in Aalesund, Norway. Just like how ‘Aalborg’ in Denmark can be written as ‘Ålborg’, so too can Aalesund be written as Ålesund. Again like Aalborg, Aalesund is a port town. It is the main city in the Sunnmøre district (the most southernly traditional district of Møre og Romsdal. To throw in some Norwegian translation, ‘Møre og Romsdal’ is literally ‘Møre and Romsdal’ (Møre refers to ‘Nordmøre’ (‘North-Møre’) and ‘Sunnmøre’ (South-Møre)), and ‘Romsdal’ is a district in roughly the same area. Of course, the presence of Sunnmøre brings us back nicely to the topic at hand. Aalesund. A town in Norway. As has rapidly become the tradition, here is a map of Aalesund.

It is at the entrance to the ‘Geirangerfjord’, and as we can see very clearly, is one of numerous areas that are islands, from which, going northernly, the Norwegian Sea is found. Though it might look small and insignificant on the map, it’s actually Norway’s 17th most populous city (okay, maybe there’s a reason it looks so insignificant…), with a population of just over 47,000. To put it into perspective from a UK point of view – that’s roughly the population of Perth. (A small tangent, but interesting nonetheless – both the Canadian and the Australian Perth were named after Scotland’s Perth!)

According to ‘Heart My Backpack’, Aalesund is “the most beautiful Fjord city”; the pictures and reviews about it would certainly suggest this to be a fair assertion. Aalesund is famed for its ‘Art Nouveau’ district (which just so happens to be one of the first things that comes up when researching Aalesund) after a 1904 fire had destroyed the city. This wasn’t just any fire – though not quite comparable to the Great Fire of London in 1666, it started in the factory of ‘Aalesund Preserving Company’ in what is now ‘Nedre Strandgate 39’ (Lower Street Gate 39). I looked up Nedre Strandgate 39 on Google Street View, and it has an absolutely beautiful view. I mean, look at it. Ship or no ship – I’d go to Aalesund just to walk down that road.

Anyway, there was a big fire. Only one person supposedly died in the fire (though 10,000 or so (of the roughly 11,000 inhabitants at the time) had to seek shelter or evacuate). The person who died was, according to Wikipedia, an “old lady who went back into her house to get her purse”. There isn’t a citation for this statement, so I won’t make any judgements on the truth, but in any case, I feel sorry for that lady. Given how they’ve now reconstructed the city, historians – perhaps naturally – are of the common consensus that the fire has become positive in terms of the city’s development. There is in fact a museum about the Art Nouveau – ‘Jugendstilsenteret’ (‘youth style centre-the’ (i.e. ‘the centre of youth style’ [‘youth style’ = ‘Art Nouveau’]). Typically, I wouldn’t speak too much about the linguistic aspects of Aalesund just yet, but I just want to express my admiration for the fact that this Norwegian museum contains words from the German magazine ‘Die Jugend’ in their name, but which focuses on Art Nouveau – a wholly French term. Mål er forlokkende!

Anyway, that leads me on nicely to the linguistics of Aalesund itself. Remember how I mentioned eels at the end of my post about Aalborg, and how they probably had next to nothing to do with the etymology of Aalborg. Well, in Aalesund, eels actually probably play quite a vital role. You see (and this is where it gets exciting!), for this to properly work I am now going to switch to writing Aalesund as ‘Ålesund’. In Old Norse, it was known as ‘Álasund’. Though Norwegian no longer uses the ‘Á/á’ letter, such a letter has existed in Icelandic to this day. (You knew it would come up at some point!). Pronounced somewhat like the ‘ow’ in ‘cow’, or in IPA terms, [aʊ], it is retained in Icelandic but has changed where Norwegian (and, as far as I’m aware, Danish and Swedish equally) is concerned. I scoured around to find an academic paper which explained this much more professionally, but couldn’t find one quickly. In any case, the letter ‘á’ developed over time in Norwegian, now being represented by ‘å’ and having a slightly different sound. Álasund can be split into Ál – a – sund. Now, the ‘ál’ section is where the reference to eels comes in. Though Norwegian doesn’t typically employ grammatical cases in the same way nowadays, Old Norse did have cases (and our good friend Icelandic is the only genealogically Norse language to fully retain grammatical cases in the standard forms). So, the ‘ál’ was likely from the plural genitive form of ‘áll’ (‘eel’) in Old Norse. For those of you who aren’t sure, the genitive, at least in this situation, refers to possession (i.e. ál would be ‘of eels’.). Then, the ‘sund’ is nice and simple – it means either ‘strait’ or ‘sound’. Funnily enough, both make grammatical and logical sense altogether – ‘strait of eels’ and ‘sound of eels’. Over time, of course, the languages changed, and so now we have Ålesund (and have done so since around 1921, before which it was written ‘Aalesund’.)

So there you have it. Aalesund. Ålesund. A strait of eels.

Word 5: Aalborg

I’ve only analysed 4 words so far. There has been one proper noun and already, on the 5th word, we happen upon another. Aalborg. Or Ålborg. Again, a location in Europe. I will do a very similar process to the one I did with Aachen – introduction, map, discussion about Aalborg itself, and then the linguistic aspects about its name and maybe some other things.

Aalborg, as I’ll generally refer to it because typing out Alt-0197 every time could get tedious, is a seaport in North East Jutland, in Denmark. There is something that has to be noted – there is the city of Aalborg and the municipality of Aalborg. Hopefully, it will be obvious which is which. If not, I’ll try and make it obvious. This is, more precisely, where Aalborg is situated; you can see its quite close proximity to the seas all around it. If you know much about Jutland, you’ll know that it’s a peninsula, and as such is in a somewhat precarious location meaning that it has a Danish part and a German part, be it socially, historically, politically… Moreover, it has had a somewhat curious history, considering Jutland more generally as opposed to just Aalborg. Though Denmark has seemingly attempted to remain neutral throughout the World Wars, it didn’t prevent there being a ‘Battle of Jutland’. Before even relatively modern history, Jutland and its area, the Cimbrian Chersonese, was likely home to various tribes – namely, the Teutons, the Cimbri and the Charudes. This is about Aalborg itself though, so I shan’t talk any more about Jutland. Partly because I don’t want to make myself sound knowledgeable about Jutland when, I’ll be completely honest, I’m really not.

Aalborg contains around 200,000 people in the entire municipality, making it the fourth most populous city in Denmark. Something I do like about Aalborg’s fundamentals is that twin cities tend to be in other countries (for example, the twin town of Gosport, where I’m from, is Royan, on the western coast of France). In this case though, the twin city of Aalborg is in the same municipality (Municipality of Aalborg), not just the same country! Aalborg’s twin city is Nørresundby, which is 600 metres away from Aalborg, over the long-documented Limfjord. That in mind, it also has close links with 33 other towns and cities, including Galway in Ireland, Edinburgh in Scotland, Lancaster in England, and the capital cities of Latvia and Lithuania – Riga and Vilnius respectively. This isn’t necessarily the same as being twin towns and cities, but the links are close enough that many youngsters from these various cities take part in an annual competition called ‘Ungdomslegene’ (or ‘Youth Games’). That’s rather wholesome if you ask me. Jeg skulle deltage i ungdojmslegenet.

It’s a fairly noteworthy city by many accounts – Siemens Wind Power is based here, and a study by the European Commission found people in Aalborg to be most satisfied in Europe with their city. In terms of its major landmarks, it’s not necessarily the most well known place in the world at first glance; that is to say, no names jump out as being considered widely sacred and must be protected or anything. As with all locations though, however big or small, it has its history. The Aalborghus castle (literally, ‘Aalborg House’ – yay for North Germanic languages (cf. hús [house in Icelandic]), built in 1550, is a half-timbered (bindingsværk) castle. It’s not massive, but reflects quite nicely the general architectural style we might expect from such a city. Other notable facets of Aalborg worth mentioning are Karolinelund, a theme park since closed (as of 2010), though it is now a cultural park which ‘Visit Aalborg’ claim demonstrates perfectly how “niche culture is rising in Aalborg”*, Aalborg Airport, an airport used both commercially and militarily, and, amongst many others, the Aalborg Historical Museum and Aalborg Museum of Modern Art. What has to be said for sure is that Aalborg is a rising community in virtually all ways. There are ice hockey clubs, handball clubs, rugby clubs – the works! A trip to Aalborg certainly wouldn’t be wasted, and there are numerous ways to get there, with Aalborg Railway Station connecting between North Jutland itself, and the rest of Denmark. Plus, well, there’s always Aalborg Airport.

Now for the linguistic discussion of Aalborg. Much like Aachen, with its -en ending, and its similarity to the German verb ‘Aach’, Aalborg is wonderfully easy to deconstruct. As with many Scandinavian place-names (and here comes my Foundation Icelandic knowledge – thanks to my wonderful Icelandic teacher!) the roots of Aalborg can be traced to Old Norse. The first likely mention of Aalborg in any form is in the name ‘Alabu’ or ‘Alabur’ in around 1040. Hardacnut ruled at this time (and interestingly, ruled in England from 1040 until 1042). Harthecnut in Danish is ‘Hardeknud’ and means ‘Tough Knot’. (The North Germanic languages can really be amazingly similar to English, even if they might sound incredibly different to the modern Anglophone ear). A basic understanding of Nordic language change makes it easy to see how we have ended thus far with ‘Aalborg’. ‘Al-‘ has become ‘Aal-‘, and ‘bur’ has become ‘borg’. Pronunciation-wise, I’d propose that they’re not too different; if one listens to modern Danish (which is notoriously difficult for non-natives to pronounce, then the ‘-rg’ [as in ‘borg’] sounds not too dissimilar from the Icelandic ‘ur’ [as in ‘góður’]. Generally, Icelandic is much more prone to retaining the sounds of Old Norse than the more central [in Scandinavian terms, anyway] languages are. ‘Borg’ itself simply means ‘castle’ in Danish, though curiously, in Icelandic, it means ‘city’. It can mean ‘stronghold’ or ‘castle’ in Icelandic too, though I’d hazard a guess at this being slightly more metaphorical than literal. I could be completely wrong though, so do tell me if I’m wrong! If we were to split up ‘Ålborg’ into ‘Ål’ and ‘borg’, we would literally get ‘Eel Castle’.

And whilst Ålborg, however you wish to write it, doesn’t seem to be at all related to eels, it would be pretty awesome if it was!

Farvel.

Word 4: Aah

The fourth word [according to my loose definitions )that is listed in the dictionary (or at least, the website ‘Dictionary.com’) is ‘aah’. ‘Aah’ indeed means what you think it means – an interjection to denote surprise, delight, joy etc.

Is this truly a word? I’m not sure. However, there are 3 parts of speech that ‘aah’ comes under according to Dictionary.com.

- Interjection – ‘Aah, now THAT’S what I call music!’

- Noun – ‘they all gave an ‘aah’ when they saw the chihuahuas.’

- Verb – ‘As the fireworks crackled, the children oohed and aahed.’

Now, as can be very clearly seen… this is an intriguing word in a number of ways. The first is the spelling. Each different ‘aah’ is spelt in different ways, and each has different connotations. ‘Aah’ is different to ‘aww’, which is different to ‘argh’, which is different to ‘awe’, which is different… the list goes on. But for this instance I’ll discuss ‘aah’.

I wasn’t sure how exactly to begin the analysis of ‘aah’ for this blog post. In fact, I’ve rewritten this exact sentence about 6 times before this version. Nonetheless, here I go. I will begin – and quite possibly end – by considering the aspects of this word with relation to each of the parts of speech given above. Thus…

The first is the use of ‘aah’ as an interjection. This is undoubtedly the first type that would come to mind, given that ‘aah’ is objectively a lot more common in spoken situations than in the written word. That’s not to say it doesn’t exist in written form – there are thousands of books from all decades and centuries that will contain the word ‘aah’, it’s probably used in this way in texts millions of times a day, etc. – but in most instances that it’s used, it’s no doubt replicating the spoken interjection. Certainly, the noun and verb forms are just grammatical adaptations of the interjection, such that it fits syntactically into a sentence (and as such has been nominalised – turned into a noun – or verbed – yes that is a word). I made a note above about how different forms of this interjection are written differently. Here, I will make the very simple assertion that this interjection spelling – ‘aah’ – is arguably the most broad, insofar that it doesn’t *specifically* alert to us what exactly is being ‘aah’-ed. With that also, it is fair to say that this ‘aah’ is just pronounced [ɑː]. Or, to be technical, it is a lengthed open back unrounded vowel. (I get mixed up with the vowels, but I checked it. It is an open back unrounded vowel.). In any case, if you just say [ɑː] in different ways, then you’re basically going through the different ways it can be pronounced – and each of these pertains to different situations.

The noun form is pretty much just the same word, but syntactically in a noun form.

The verb is, well, the verb form of the interjection.

That’s all there really is to those two discussions.

There is one thing I should note though, is that, as a verb, it seems to be in two main collocations (where two words complement each other as a set phrase, as in ‘fish and chips’, ‘Starsky and Hutch’, etc.), both of which are really quite different in meaning. They are ‘ooh and aah’ (primarily used with fireworks in my experience), and ‘um and aah’ (describing a state of being unsure about a certain decision; as in the case of ‘I was umming and aahing about whether to buy it or not’). I personally prefer the use of ‘aah’ in the latter, possibly because I much prefer the phrase itself.

I could discuss this in much further detail. Do I want to? Not really. Time to move onto more exciting words, methinks!

Aah, the joys of blogging.

Word 3: Aachen

3 words in and we come to the first proper noun of the list (partly because a) I’m including proper nouns and b) I’m not including acronyms). So, the first proper noun is ‘Aachen’. Well, that’s much less confusing to write in inverted commas than ‘Aa’! Interestingly, in the list, as can be seen in the image below, ‘Aachen’ is written lowercase, as ‘aachen’, which raises some small curiosities about headwords and the importance of capitalisation. Similarly, acronyms which would otherwise be capitalised are lowercase. My guess is that it’s just the formatting and/or a stylistic choice, but who knows, maybe there’s an actual reason for it.

‘Aachen’ is a city situated in West Germany, in North Rhine-Westphalia. Here is a map showing where. I haven’t been to Aachen, but there is a town called Koblenz just under 2 hours away that is wonderful. I recommend it.

Interestingly, Aachen’s name in French is ‘Aix-la-Chapelle’; I’ve heard of the latter, but never would I think they’d be the same place. It’s also a ‘spa town’ (the word ‘Spa’ itself coming from ‘Spa’, a town in Belgium). This means that the town is built upon or around a mineral spa. Nonetheless, this is more about ‘Aachen’, and less about ‘spa’. I doubt I’ll ever get to ‘spa’, but for now, he we sp-are in Sp-Aachen. That was terrible, I know. Sorry.

Interestingly, Aachen’s name in French is ‘Aix-la-Chapelle’; I’ve heard of the latter, but never would I think they’d be the same place. It’s also a ‘spa town’ (the word ‘Spa’ itself coming from ‘Spa’, a town in Belgium). This means that the town is built upon or around a mineral spa. Nonetheless, this is more about ‘Aachen’, and less about ‘spa’. I doubt I’ll ever get to ‘spa’, but for now, he we sp-are in Sp-Aachen. That was terrible, I know. Sorry.

Though this blog primarily focuses on linguistic aspects of words and things, a bit of background of Aachen is at the very least interesting. Aachen appears to be an incredibly important city in German, and indeed more generally Western European, history and culture. So important, in fact, that there are several pages on Wikipedia all about Aachen, including a timeline of its history. I won’t bore you with the details, but in 1306, it became a “Free Imperial City of the Holy Roman Empire”. As someone whose historical interests lie in, primarily, genealogical research and Ancient Greece and Rome in the earlier Julio-Claudian periods, this is something that I probably wouldn’t typically look further into. Another page says that it was declared this in 1166. Whatever the year, it was a “Free Imperial City of the Holy Roman Empire”. Well done, Aachen. In the centuries after, it flourished more and more – in 1795, the population was just over 23,000, and just 100 years later (in the exact same year that the Electric Tramway opened, it was just over 103,000). In 1825, the ‘Theater Aachen’ was opened; in 1849, the news agency Reuters started operating there (and still exists to this day), and, from 1905 onwards, Aachen saw the introduction of a railway station (Hauptbahnhof), Tivoli Stadium (now Old Tivoli), the Aachen University of Applied Sciences, and many more besides.

Enough about Aachen itself though. Let’s look at Aachen from a linguistic perspective. I have already supplied you with the information about Aachen being known as ‘Aix-la-Chapelle’ in French (and consequently the same in English), but I haven’t properly discussed the etymology of Aachen, or why it’s Aix-la-Chapelle en Français. But now it is time. Or rather, ‘jetzt fühle ich mich bereit’. (Danke, Ari, für die Übersetzung!). Aachen is etymologically like quite a lot of place names, in that it derives from a quality about, or information about, the area itself – and it is now that I delve into one of my favourite, duly underrated areas of linguistics: onomastics. ‘Aach’ is a German word meaning ‘river, stream, etc.’. [‘Aach’ itself is from the Old High German word ‘ahha’ (cognate with ‘aquae’, Latin for ‘springs’). ‘Ahha’ isn’t a word on Dictionary.com (unless you count the acronym ‘AHHA’ – ‘after hours home avoider’ (which I’m inclined to think is something they’ve made up)), but its similar [though completely unrelated word] ‘aha’ is.

Anyhow, very simply, ‘Aachen’ means ‘river’. It’s not much more complicated than that in the German. The French name is a bit more historically interesting, but as ‘Aix-la-Chapelle’ has its own Dictionary.com entry, I’ll discuss that at a later date. In the future at some point. Maybe.

Auf Wiedersehen.

Word 2: Aa

Aloha, nā mea heluhelu!

I didn’t think that this early on, we’d come across Hawaiian loanwords. But there we are! Aptly, the “Lingua Franca Challenge” that I’m a part of on Facebook has begun Hawaiian… the stars have aligned! No, I don’t know how to say that in Hawaiian.

‘Aa’ is an anglicised form of the Hawaiian <‘a’ā>. I’ve used guillemets there because inverted commas could be confusing.

Apparently, ‘aa’ is a “basaltic lava having a rough surface”, and can be compared to ‘pahoehoe’ (also of Hawaiian origin meaning “basaltic lava having a smooth surface”). What a great word.

The IPA for the Hawaiian word ‘a’ā is /ʔaˈʔaː/ – essentially, a glottal stop (like dropping the ‘t’ in ‘butter’) before a long ‘ah’ sound as in ‘car’, then duplicated (though the second ‘ah’ sound is slightly longer, shown by the /ː/.

Though it’s only 2 letters long, the structure of this word is very interesting. ‘Aa’ in English just seems like a complete unit of letters when we know its semantic qualities (that is, the meaning of ‘aa’). However, in Hawaiian, this is very different. You see, Hawaiian is an isolating language, which in its simplest form, means that it doesn’t use “inflectional morphology” to show tense, plurality, etc. For example, English uses the ‘inflectional morpheme’ of ‘-s’ in most regular cases to show plurality (cat -> cats) with certain conventions such as ‘-es’ if the noun ends in a sibilant (that is, <s>, <sh> and <z>). There are several others, but they’re not really important for this.

Anyhow, ‘aa’ is written as <‘a’ā> in Hawaiian. To make this word much easier to understand, we can put it in a morphology tree, like so:

I’ve included the IPA for clarity’s sake. The lowercase sigma (σ) simply represents the entire structure of the word here (though I’m pretty sure that’s strictly for phonology but nonetheless I’ve included it). Now, anyone would no doubt notice that the a with the macron (ā) is the longer /a:/ form. These are two different units of meaning here. <‘ā> means “active, as a volcano”. [wehewehe.org]

That is, the unit of <’ā> denotes something that is active. Now, when looking up just <’a>, I don’t necessarily come across anything to do with volcanoes or lava. This small word has nonetheless given us an insight into how Hawaiian morphology works.

If there’s anyone who is well-versed in Hawaiian morphology or syntax, or even speaks it, I’d love to hear from you!

Word 1: ‘A’

It’s a curious idea to call ‘a’ (and its similar one-letter counterpart ‘I’) a word. Qualitatively defining what a ‘word’ actually is is complicated, but I’m not going to go down that route right now (though here is a good Tom Scott video which details the issue very well).

In any case, let us refer to ‘a’ as a word. In English, it has a very useful, and equally interesting, position in many ways. Not only is it the first letter of the alphabet, it’s also the ‘indefinite article’.

For any non-linguists reading, this is just that we use ‘a’ before a common noun or noun phrase (dog, chair, vegan sausage roll, etc.) to imply that there is one of said noun. It seems a pretty simple word then. And fundamentally, in English it is. It simply precedes a singular noun. So ‘I sit on a chair’ is perfectly fine, but we probably [sociolinguists and dialectologists…?] wouldn’t say ‘I sit on a chairs’, nor would most of us be silly enough to sit on multiple chairs at once because, y’know, health and safety.

“But what about phrases like ‘a good few men’? ‘Men’ is plural and not singular, but we still use ‘a’…”

And such a simple query illustrates just how beautifully complex language can be. In ‘a good few men’, we essentially have what could be considered an unusual situation here; ‘a’ with a plural noun. In fact, we could very well say that ‘a’ seems to be pretty useless here – ‘good few men’ could be reasonable. Compare the two below though:

I saw a good few men over there.

#I saw good few men over there.

We – or at least I – think that the second sentence doesn’t sound right (which is why I’ve included the octothorpe there – it’s a syntactically fine phrase in English, but doesn’t really sound right). We almost want to include ‘a’ without even thinking about how woefully absurd this might be. And this is simply because the ‘a’ doesn’t relate to the ‘men’ here; it relates to ‘few’ – an adjective expressing number – insofar that ‘a’ doesn’t necessarily exist as its own element here. It is part of the greater phrase ‘a few’. If we were to take out the adjective ‘good’, we could say ‘a few men’ – perfectly fine – and ‘a good few’, presuming that we already know what we’re referring to, is equally fine. Saying ‘the good few men’ would be perfectly fine too, employing the definite article ‘the’ instead of indefinite ‘a’; pragmatically though, ‘the’ implies something very slightly different to ‘a’ (as no doubt I may end up discussing in the future… at some point… maybe.)

Whew. So that’s the fundamental point about ‘a’ as a word in a sentence.

But I want to look at something else. And this I could do in GREAT detail, but because it’s 23:39 and I’m not sure whether there are any limits to WordPress blogs – or how much you can fathom reading about a single letter of the alphabet – I’m going to keep it fairly short, and focus on how ‘a’ is pronounced when on its own. I’ll likely be using IPA a fair bit in this small discussion, but you needn’t worry – I’ll try as best I can to explain too.

So think (yay, audience participation) about how you would pronounce ‘a’ in something as simple as ‘I ate a salad yesterday’.

There’s the typical way that we would pronounce the ‘a’ here; as an unstressed vowel. Personally, I pronounce this as something like [don’t freak out just yet]:

/ɑɪ eɪʔ ə pɪd͡ʒən jɛst̪deɪ/

See, I said you needn’t freak out.

But just focus on this symbol – /ə/ – a favourite amongst linguists. And, seemingly, one of the only IPA symbols that foreign language phrase books will happily use in their pronunciation guides (much to the happiness of us linguists). Essentially, this sound – a ‘schwa’ – appears very regularly in English. Hundreds of words contain it – ‘zebra’, ‘Fanta’, even ‘the’ – all contain it at the end.

It’s an unstressed vowel; which just, kinda, exists, at least in English.

But what about the pronunciation of [eɪ] for ‘a’ on its own? That is, the ‘ay’ sound in ‘day’, ‘bake’, ‘grey’, etc.

That can exist too, particularly if we have a filler after it. In the sentence ‘I ate a, um, pigeon yesterday’, the indefinite article is much more likely to be pronounced with the [eɪ] as in ‘yesterday’ than the [ə] as in ‘pigeon’. Similarly, it can be pronounced as [eɪ] if we’re emphasising (that in itself being a whole new discussion point…!). Contextually, we might emphasise that its singular by using ‘one’ instead of ‘a’, but it can certainly change pronunciation. Harrison (2012) summarises this well in ‘Perfect Pronunciation, by Jingle!’ (quite an ironic book title to use as the first written source for a linguistics blog, but nonetheless it’s good for this):

“When you pronounce the indefinite article “a” in isolation, you are sure to pronounce the “a” as the first letter of the alphabet… in connected speech, it generally becomes a schwa unless you want to emphasize the phrase”. [Harrison 2012]

It essentially just reiterates exactly what I said above – phonologically speaking, such a short word can be quite interesting.

That’ll be it for now, I think. So what have we learnt from this first ever post on ‘An Awesome Alphabet Analysis’?

Well, a good few things about a simple letter/word, but fundamentally we have learnt that ‘a’ is a beautiful thing.

References:

Harrison, S. 2012. Perfect pronunciation, by Jingle!. Indiana: iUniverse. [Accessed 10/06/2019]. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/y5x9fpor

Tom Scott. 2015. What counts as a word? [Online]. [Accessed 10/06/2019]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m8niIHChc1Y